Last June, the Pew Research Center released a report entitled, Political Polarization in the American Public. Its opening sentence was alarming: “Republicans and Democrats are more divided along ideological lines – and partisan antipathy is deeper and more extensive – than at any point in the last two decades.” Obviously, people will have principled differences about big ideas and public policies, but those principled differences seem to be negatively affecting personal relationships. “Not only do many of these polarized partisans gravitate toward like-minded people,” the report went on to note, “but a significant share express a fairly strong aversion to people who disagree with them.”

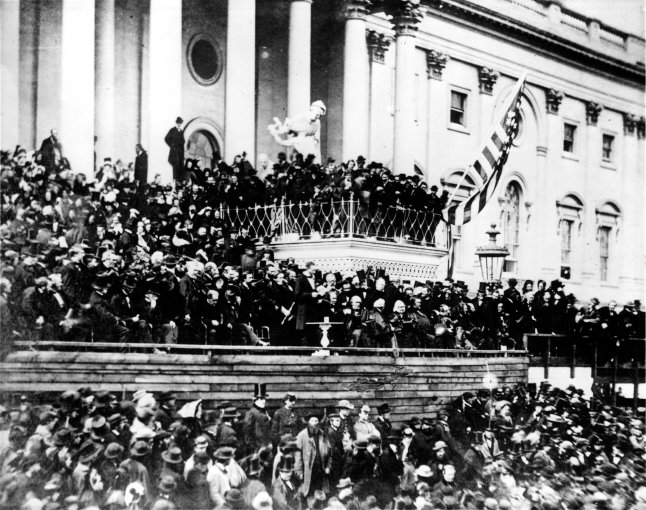

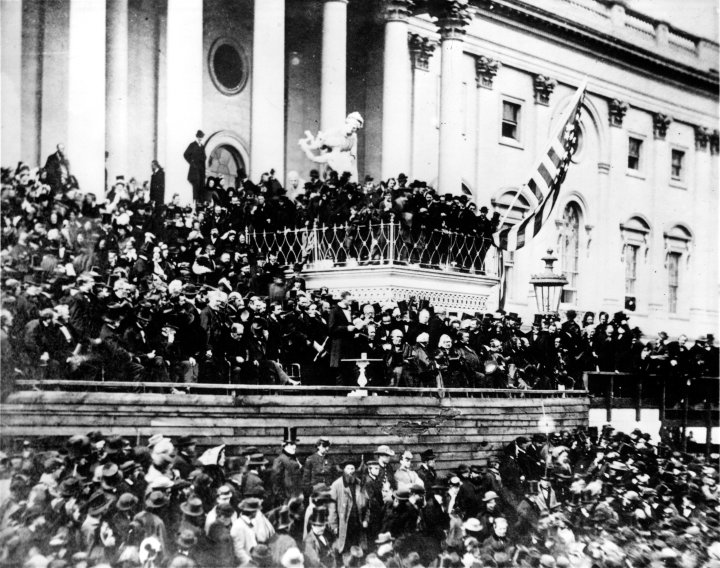

Today is the sesquicentennial of Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. That speech addressed ideological division and personal antipathy so severe that they had resulted in a civil war. Might Lincoln’s words from 150 years ago still speak to us today?

The Progress of Our Arms

“The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends,” Lincoln began, “is as well known to the public as to myself; and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.” Lincoln’s high hope would be realized in little over a month, when Robert E. Lee surrendered to U.S. Grant on April 9 at the McLean House in Appomattox, Virginia. At the time of the inaugural, victory was just around the corner, but not yet in sight. Neither, of course, was Lincoln’s assassination, which took place on April 14.

The Role of Slavery

Lincoln continued his address with a reminder of the cause of the war. “One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest.” Lincoln was not saying, it should be noted, that the Civil War began as a fight to abolish slavery. As Lincoln wrote Horace Greeley on August 22, 1862, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” The abolition of slavery became an explicit war aim on January 1, 1863, when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. But at the outset of the war, preserving the Union, not freeing the slaves, was Lincoln’s stated goal.

Nonetheless, the reason the Union was threatened was because of differences over slavery. As Lincoln noted: “All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.”

Because these clashing interests could not be resolved peacefully, “the war came.” Both sides expected “an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding” than the long slog of violence that actually ensued. In a nation of 32 million, 625,000 soldiers died—nearly two percent of the entire population! To put these military casualties in perspective, consider this: Civil War military casualties account for nearly half of all U.S. military casualties from the Revolutionary War to the present day.

The Role of Providence

Given Lincoln’s commitment to Union and emancipation, and given the war’s slaughter, his listeners undoubtedly expected Lincoln to issue a rousing denunciation of the Confederacy. But that’s not what they got. Instead, what they heard may be the most profound theological meditation on the Civil War ever given:

Lincoln began by noting the religious kinship of the North and South: “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.” At a recent visit to a Civil War battlefield, I purchased replicas of prayer books printed for use by Union and Confederate soldiers. With minor exceptions, the prayer books are identical. The hymn selections—indeed, the very numbering of the hymns!—shows that opposing soldiers sang from the same hymnal.

Speaking as a Union partisan, Lincoln pointed out the oddity of this religious kinship: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces,” but paraphrasing Jesus, he counseled listeners, “let us judge not that we be not judged” (Matthew 7:1). Obviously, he pointed out, contradictory prayers cancel each other out. “The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully.”

But then, rather than saying that the prayers of the Union had been answered in the main because God was on their side, Lincoln said this: “The Almighty has His own purposes. Once again, quoting Jesus, he continued, “Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” (Matthew 18:7). And this led to an indictment of both North and South for their participation in the offense of slavery:

If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? [Emphasis added.]

The answer, of course, is no. The war came by the providence of God. Lincoln continued

Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether” [Psalm 19:9].

Americans have become accustomed to presidents invoking God’s blessing on our nation, its interests, and even its wars. Lincoln was the rare politician who invoked God’s judgment against the very country he led.

A Just and Lasting Peace

I can’t help but wonder whether Lincoln’s hearers were offended by his even-handed criticism of both the North’s and the South’s roles in the offense of slavery, not to mention his invocation of divine judgment against them both as an explanation for the war.

But if they were offended, they must have been astonished by his concluding words:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Without giving an inch on “the right”—that is, on the North’s efforts both to preserve the Union and free the slaves—Lincoln called a nation still at war to replace “malice” toward its enemies with “charity.” He called on it to move from killing, and fighting, and war to healing, and caring, and peace.

Lincoln and Christians Today

It is Lincoln’s transcendence of the passions of his day that is so relevant to all Americans today. Somehow, he found a way to affirm the ideology of Union and emancipation without practicing personal antipathy to its Southern critics. He sought “the right” without becoming self-righteous in the process. Precisely because he could see Northern complicity in Southern slavery, he warned against judgmentalism and encouraged “malice toward none” and “charity for all.”

His words have a special relevance for Christian partisans because today—as in his own day—faith (or the lack of it) is a driver of ideological division. American Christians should seek to implement “the right” in public policy, “as God gives [them] to see the right.” We should be critical in our analysis of the “particular and peculiar interest[s]” that misshape our republic, even as we are cognizant of the interests that misshape us too. And we should be wary—as Lincoln was, and so many theologians in his day were not—of so easily invoking God’s blessing on our side. (On the North’s and South’s equally fervent but mutually contradictory Christian partisanship, see The Civil War as a Theological Crisis by Mark Noll.) With Lincoln, American Christians need to remember, “The Almighty has His own purposes”; “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.” They apply equally to us as they do to others.

Finally, with Lincoln, American Christians need to remember that in all our controversies—some of which cannot be avoided, the goal of our actions is “a just, and a lasting peace”: the all-encompassing wellbeing which God created us to experience with one another, and through Christ, with Him. True peace requires that justice—“the right”—prevail. But it also requires that peaceableness—“malice toward none,” “charity for all”—be our stance toward others, even in the midst of our conflicts with them.

Firmness in the right. Malice toward none. Charity for all. These are principles all Americans—especially American Christians—would do well to remember as they seek to influence the public square.