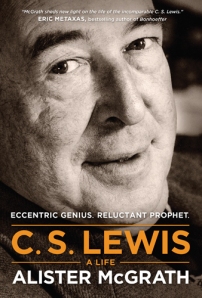

McGrath, Alister. 2013. C. S. Lewis—A Life: Eccentric Genius, Reluctant Prophet. Carol Steam, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

McGrath, Alister. 2013. C. S. Lewis—A Life: Eccentric Genius, Reluctant Prophet. Carol Steam, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

C. S. Lewis—Jack to his friends—looms large in the American evangelical mind.

On the one hand, this is surprising. A communicant in the Church of England, Lewis was generically orthodox but not specifically evangelical in theological or spiritual emphases. His closest lifelong friends were a homosexual Unitarian (Arthur Greeves) and a traditionalist Roman Catholic (J. R. R. Tolkien). And he drank and smoked prolifically, at one point having a barrel of beer in his rooms at Oxford for the use of his students.

On the other hand, Lewis’s influence on American evangelicals is not surprising. After World War II, American neo-evangelicals shook off their Fundamentalist separatism and irritability and began to actively engage culture with an eye toward changing it. Lewis—the Oxford don who wrote well-regarded studies of medieval English literature, well-written works of Christian apologetics, and well-loved children’s stories—modeled the kind of influence evangelicals wished to exercise on culture high, middlebrow, and popular.

Writing about Lewis is thus something of a cottage industry among American evangelicals, with new titles on this or that aspect of his thought or life appearing regularly. Alister McGrath’s new biography of Lewis is part of that cottage industry—though McGrath is a British evangelical—but nonetheless a welcome addition to it. The broad outlines of Lewis’s life have been sketched before, by Lewis himself (in Surprised by Joy) and by others. What distinguishes McGrath’s biography is the use he makes of Lewis’s collected letters, published in 2004 (volumes 1 and 2) and 2007 (volume 3) by Walter Hooper, Lewis’s literary executor. A careful reading of these letters leads McGrath to argue, against Lewis and Lewis scholars, that Lewis misremembered the date of his conversion to Christianity, placing it in 1929 when it actually occurred in 1930. Whether McGrath’s letter-based argument will win the day is an open question.

McGrath organizes his narrative of Lewis’s life in five parts: “Prelude” (1898–1918), “Oxford” (1919–1954), “Narnia,” “Cambridge” (1954–1963), and “Afterlife,” which focuses on the ongoing influence of Lewis, especially among American evangelicals. He weaves together Lewis’s inner world of ideas and outer world of circumstances into a warts-and-all tapestry. Those who have only read Lewis’s works—whether scholarly, apologetic, or fictional—may be surprised at some of the warts.

The two biggest surprises, at least to readers unacquainted with Lewis’s life, may be his relationships with two women, first Mrs. Jane King Moore, and then Joy Davidman. The former was the mother of Lewis’s deceased war buddy who was financially supported by him from the end of World War I until her death in 1951. The same age as Lewis’s deceased mother Flora, Mrs. Moore evidently filled a maternal void in Lewis’s life. (His relationship with his father Albert was strained through his adult life.) At some point, beginning perhaps in 1917, their relationship was also sexual, probably ending prior to his conversion. From 1930 until her death in 1951, she lived with Lewis and his brother Warren at their home, The Kilns, which was deeded in her name.

Joy Davidman was an American divorcee, ex-communist, and convert to Christianity, whom Lewis married, abruptly and without notice to friends, in a civil ceremony in 1956. The marriage began as a legal convenience, allowing Davidman and her two sons to remain in Oxford once their residence permissions expired. But it grew into real love. Indeed, the death of Davidman by cancer in 1960 brought forth A Grief Observed, Lewis’s harrowing account of loss.

I mention these two relationships in particular because evangelical readers of Lewis can be so impressed with Lewis’s apologetic for Christianity and literary imagination that they forget he was a flesh-and-blood human being, with all the sins and weaknesses of the race. We—I speak as an American evangelical—cannot idolize the man, which he wouldn’t have wanted anyone to do anyway.

By the same token, however, we shouldn’t discount Lewis’s real literary achievements. Lewis’s academic works—especially on Edmund Spenser and John Milton—can still be read with profit. His apologetic works still offer suggestive critiques of atheism and naturalism. And his fiction can still delight and instruct both children and adults alike.

I highly recommend Alister McGrath’s biography of C. S. Lewis. It humanizes the legend and contextualizes his achievements, but it doesn’t debunk him in the process. Lewis, being dead, can still speak—to American evangelicals and to others. McGrath’s biography gives his life and ideas an earthy voice for a new generation.

P.S. If you found this review helpful, please vote “Yes” on my Amazon.com review page.